The Drawings of André Masson

via Hyperallergic

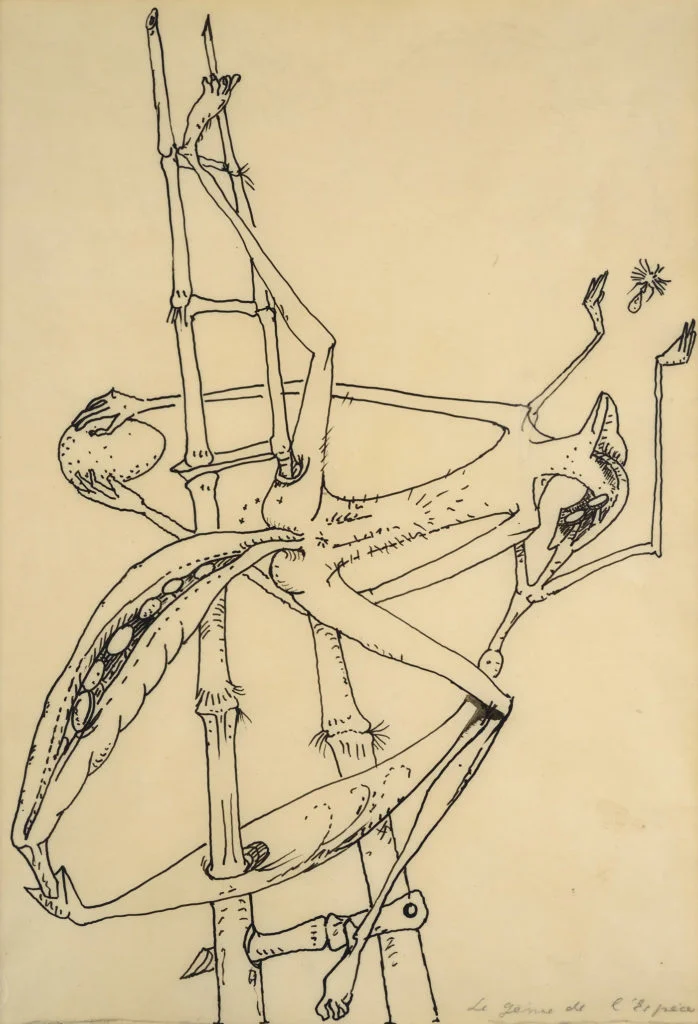

PARIS — In the polyvalent and multilayered drawings of André Masson, you can sense a free hand in love with its own movement, but not with itself. There is a speeding, automatic, ritualistic, and revelatory mode of iconographic mark-making in all the drawings in André Masson dans l’antre de la métamorphose at Galerie Natalie Seroussi, which seem to flow from one key piece: the sex-machinic “Automatic Drawing” (1924). This jittery work sets up a conflict between hard angles and the feminine litheness of curves. Aggressive lines cut through the supple curves of a centered, nude woman made of Francis Picabia-like cyborg parts. The drawing evidences an artistic method that plays on the line between chaotic control and non-control, aiming toward a capricious alliance that likens mechanical grinding to organic sexuality, an association that opens up both notions to mental connections that enlarge them. In this work, the subsequent cyborg woman of Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927) is already undone by disturbances she cannot contain.

An expanded field of subjects pervades the visual lexicon of Surrealism, but Masson is generally considered to have pioneered the automatic drawing technique with an opulence that borders on the decadent. Masson’s graphic automatism was a visual analogy to the écriture automatique, a writing method based on speed, chance, and intuition. In doing so, he also revealed a certain amount of reflection and artistic strategy............Continued

André Masson, “Benjamin Péret — Automatic Drawing” (circa 1925)

However, around the exact same time (summer of 1924), the English artist and chaos magician Austin Osman Spare — a late-decadent, perversely ornamental graphic dandy in the manner of Felicien Rops and Aubrey Beardsley — produced a sketchbook of “automatic drawings” featuring disembodied fabula on a par with Masson’s. Entitled The Book of Ugly Ecstasy, it contained a series of outlandish, pan-sexual creatures produced through automatic and trance-induced means. This swank book was purchased by the art historian Gerald Reitlinger, but in the spring of 1925 Spare produced another, similar volume, A Book of Automatic Drawings, which has been reproduced. Spare claimedto have been making automatic drawing as early as 1900 (when he was 14), yet he was unknown to the Surrealists. Nevertheless, the dates of his automatic drawing books parrallel Masson’s semi-automatic drawings “Benjamin Péret — Automatic Drawing” (circa 1925) and “A Louis Aragon” (1924) in uncanny ways. Masson’s beautiful, drowsily drawn “Benjamin Péret — Automatic Drawing” fluidly depicts the French poet. Like Spare, Masson began automatic drawings with no preconceived composition in mind. Like a medium channeling a phantom spirit, he let his pen travel hastily across the paper without conscious control, soon finding hints of images emerging from the abstract, lace-like web.

Like Masson, Spare claimed that twisting and interlacing lines permit the magical germ of an idea in the unconscious mind to express — or at least suggest — itself to consciousness. For Masson, artistic intentions should just escape consciousness. Although some shapes are discernible amid abstract lines, others seem to be open to interpretation, allowing viewers to use their own subconscious cues to decipher the images. In time, shapes might be found to emerge, suggesting forms.

André Masson, “La ville cranienne” (“The Cranial City,” 1939)

André Masson, “Le génie de l’espèce” (“The Genius of the Species,” 1939)