Japan, in from the Wilderness: Reiko Tomii’s Expanded Modern-Art History

via Hyperallergic

The Japanese-born art historian Reiko Tomii is one of those researchers who is both passionate about her subjects and recognized among her peers for her meticulous mapping of the cultural-intellectual terrain from which they emerge. An independent scholar who has lived and worked in the United States since the mid-1980s and has been based in New York for many years, Tomii has focused on the artists and art movements of post-World War II Japan, carefully classifying their evolution and ideas, as well as their constituent parts, antecedents and relevant affinities.

Although she admits that “art history is not a precise science,” her own approach is unmistakably fine-tuned, and she is an inventive thinker. The results and revelations of her method are well showcased in her new book, Radicalism in the Wilderness: International Contemporaneity and 1960s Art in Japan (MIT Press).

“Radicalism in the Wilderness: International Contemporaneity and 1960s Art in Japan” by Reiko Tomii (courtesy MIT Press) (click to enlarge)

In it, she takes on modern-art history’s familiar, canonical narrative, which, understandably, has long focused on the ideas, artists, movements, and milestone events that are linked to its roots territories in Europe and North America. However, Tomii does not take a crowbar to this history with the intent of forcing open its pantheon of recognized masters to make room for less well-known but attention-deserving modernists from Japan.

Instead, her objective reflects the interests of a still-evolving but ever more notable tendency among certain researchers and curators in the U.S., Europe and East Asia to examine modern art’s development with a broader, deeper, more inclusive scope.

Their new consideration of modern art’s story has brought such places as Mexico City, Rio de Janeiro, Tokyo, Osaka, Seoul, Delhi and Prague into sharper focus. (In the US, Alexandra Munroe, the senior curator of Asian art at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York has been a trailblazer in this effort since the mid-1990s. More recently, such museums as Tate Modern in London, the Stedelijk in Amsterdam and the Museum of Modern Art in New York have appointed new curators or developed special research programs to pursue this new outlook.)

Tomii’s own research and curatorial work have contributed significantly to this new, so-called global view of modern art’s history. In Radicalism in the Wilderness, she describes “international contemporaneity” as “a geohistorical concept, one that liberates us from the inevitable obsession with the present inherent in ‘contemporaneity’ as used in the English construction of ‘contemporary art’ (whose basic meaning is ‘art of present times’) and helps us devise an expansive historical framework” by means of which “a multicentered world art history” may be told. She argues that an understanding of this phenomenon may make room for overlooked or ignored currents in the story of modern art as it developed in 20th-century Japan after World War II. She also puts forth the related notions of what she calls “connections” and “resonances,” the meanings of which become self-evident as her study unfolds.

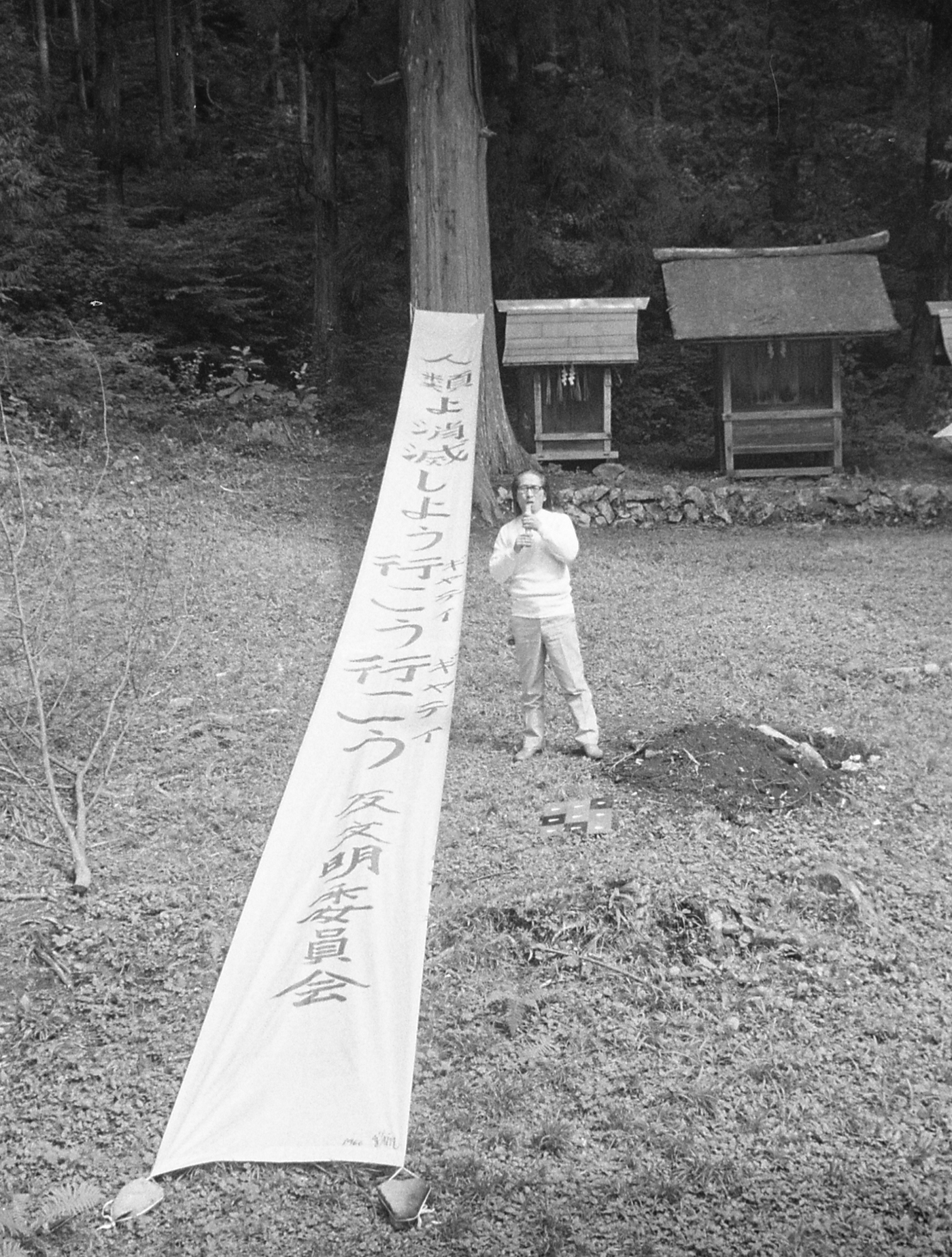

Japanese artist Yutaka Matsuzawa and his “Banner of Vanishing (Humans, Let’s Vanish, Let’s Go, Let’s Go, Gate, Gate, Anti-Civilization Committee)” (1966), at Mount Misa, Japan, 1970 (photo © Hanaga Mitsutoshi) (click to enlarge)

However, looking back at past events and examining the “international contemporaneity” of a certain moment or era from a particular vantage point is not quite the same as taking the pulse of its Zeitgeist. Instead, keen observers like Tomii are on the lookout for similar expressions, ideas, or breakthroughs that occur in different places at more or less the same time. In this way, Tomii notes, historians aiming to construct a global history of modern art must “seek out and examine linkable ‘contact points’ of geohistory,” where they will find evidence of what she calls “connections,” or “actual interactions and other kinds of links” between artists, critics, curators and other figures in the world of art, and “resonances,” which she defines as “visual or conceptual similarities” between artists’ ideas, creations or activities, even in situations in which “few or faint links existed.”

Tomii uses the examples of one solo artist and two artists’ collectives that were active in Japan in the 1960s, and whose works can be classified as conceptual art, to illustrate her observations about “international contemporaneity.” These artists’ careers offer intentional and unwitting points of contact with artists in the US and Europe. Tomii cites Yutaka Matsuzawa, who was born in 1922 in central Japan, earned a degree in architecture in Tokyo, and returned to his native region, where he later came up with art forms that reflected his disenchantment with “material civilization.”

He spent a couple of years in the US, including a stay in New York in the late 1950s, looking at art— Jackson Pollock’s paintings, Robert Rauschenberg’s mixed-media “combines” — and learning about parapsychology. Matsuzawa was interested in physics, Buddhist thought and the idea of visualizing the invisible. Back in Japan, he developed works that invited viewer-participants to “vanish” certain subjects — to make them disappear. (He once told an audience at his university, “I don’t believe in the solidness of iron and concrete. I want to create an architecture of soul, a formless architecture, an invisible architecture.”) At the exhibition Tokyo Biennale 1970: Between Man and Matter, in which both Japanese and numerous, well-known Western artists took part — a milestone, Tomii notes in retrospect, of “international contemporaneity” — Matsuzawa offered an empty room titled “My Own Death.”

Tomii also looks at the activities of The Play, a group of “Happeners,” founded in Osaka in 1967, who devised and carried out their own versions of “Happenings,” those action-as-art events that blasted the idea of the work of art as a physical object. The Play’s message, Tomii writes, “was constructive, not destructive, as their major concern was to take a ‘voyage’ away from everyday consciousness trapped in familiar space and time.” Their provocative events included erecting a huge cross made of white fabric atop a mountain (for which they intended no specific message, although it called attention to nearby urban zones’ proximity to nature), and group member Keiichi Ikemizu’s “Homo Sapiens” performance piece of 1965, in which he stood for hours like a zoo animal in a cage. A sign identified him as a representative of the human species. In 1968, The Play created a gigantic fiberglass egg, which they released into the ocean near the southernmost tip of Japan’s main island. Ikemizu told a Japanese magazine that “Voyage: Happening in an Egg” offered “an image of liberation from all the material and mental restrictions imposed upon us who live in contemporary times.”

The Play, “Voyage: Happening in an Egg” (1968), photo of performance-art event in progress (photo © The Play)