Clare Grill (American, b. 1979, Western Springs, IL, USA, based Queens, NY) - Yoke, 2010 Paintings: Oil on Linen

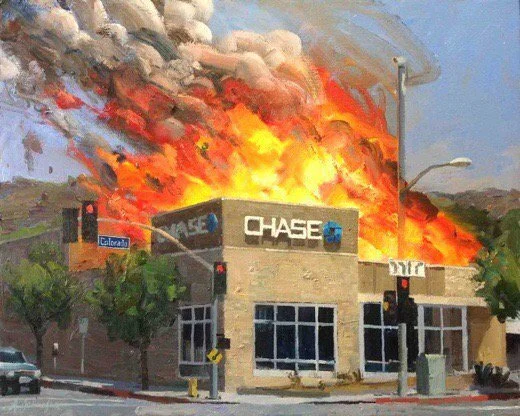

Alex Schaefer specialized in paintings of Chase bank on fire

via BoingBoing

I love Alex Schaefer impasto works depicting branches of Chase bank going up in flames in daytime. They were from a series by him called "Disaster Capitalism," and apparently the banks (and cops) would pretend he was planning acts of arson to try and make him stop painting. [via mutantspace, via Janie]

On July 30, 2011, Alex Schaefer set up an easel across the road from a Chase bank and began painting the building in flames. However, before he had finished the police arrived, asked him for his information and if he was planning on actually carrying out an arson attack on the building. Ridiculous. Later they turned up on his doorstep asking about his artwork and looking for any signs that he was going to carry through an anarcho – terrorist plot based on his paintings. If this wasn’t bad enough a year later he was arrested for drawing the word ‘crime’ with a Chase logo in front of an LA bank.

“End Bad Breath,” poster by Seymour Chwast (1968) (© Seymour Chwast)

Seymour Chwast’s Graphic Battle Against War

via Hyperallergic

A 5,000-year chronicle of human violence is the goal of illustrator Seymour Chwast’s new book project, which follows his almost six-decades of antiwar art. Seymour Chwast at War with War: An Illustrated Timeline of 5,000 Years of Conquests, Invasions, and Terrorist Attacks is currently funding on Kickstarter, while an exhibition of his antiwar work, from posters to publications, is on view at the Society of Illustrators. Seymour Chwast on War is installed amid the Society of Illustrators’s third floor dining room, with a long mural of firing tanks, crashing planes, paratroopers, and mangled human bodies presiding above the tables, while ephemera fills cases near the bar and posters line the brick walls. These include some of his more iconic antiwar art, characterized by his wry wit, like the Vietnam War-era “War Is Good Business Invest Your Son” and “End Bad Breath,” in which a green-faced Uncle Sam has the bombing of Hanoi visible in his gaping maw.

“War is Good Business, Invest Your Son,” poster by Seymour Chwast (1968) (© Seymour Chwast)

“Whether defensive or aggressive, liberating or subjugating, all wars are ultimately transgressive acts where culture and humanity are held hostage to ideology, greed, and power,” states author and art director Steven Heller in his exhibition introduction. “Although Chwast’s art won’t put an end to war, it invites us to think about the consequences — and, more important, who ultimately benefits from the spoils.”

Heller is the editor for Seymour Chwast at War with War, which is presented on Kickstarter by Designers & Books, an “advocate for books as an important source of inspiration for creativity, innovation, and invention.” The Bronx-born Chwast is often recognized for his role as a co-founder of the influential graphic design-focused Push Pin Studios, started with fellow Cooper Union alumni Milton Glaser, Reynold Ruffins, and Edward Sorel. Yet alongside his bold and colorful commercial work, he’s also long been involved in artist books, which often have a rawer style, such as his 1957 Book of Battles. His first antiwar book, it has nine linocuts representing hundreds of years of showdowns, and the current project is in a way an extension of this initial work, his illustrations in pen and ink and on woodcuts extending this history of bloodshed. A Teutonic knight spears a man in the 1283 Prussian conquest, elephants pummel people in the Punic Wars, skulls are piled high in a representation of the 1994 Rwandan Genocide, and a soldier is posed in profile in Chwast’s woodcut for the 2006 Iraq War.

Illustration of the 1994 Rwandan Civil War from ‘Seymour Chwast at War with War: An Illustrated Timeline of 5000 Years of Conquests, Invasions, and Terrorist Attacks’ (© Seymour Chwast)

The exhibition at the Society of Illustrators can be a bit awkward to peruse if you’re not there to dine below the carnage, being that some of the work is installed right above the tables and some people don’t like their lunch interrupted with random art staring (go figure). However, it’s worth a look for a glimpse into the prolific career of an influential graphic designer who has long doubled as an advocate for peace.

Illustration of the Punic Wars from ‘Seymour Chwast at War with War: An Illustrated Timeline of 5000 Years of Conquests, Invasions, and Terrorist Attacks’ (© Seymour Chwast)

Illustration of the 2006 Iraq War from ‘Seymour Chwast at War with War: An Illustrated Timeline of 5000 Years of Conquests, Invasions, and Terrorist Attacks’ (© Seymour Chwast)

‘A Book of Battles,’ Seymour Chwast’s first antiwar book (1957) (© Seymour Chwast)

GUN, “Event to Change the Image of Snow” (1970), photo of performance-art event in progress (photo © Hanaga Mitsutoshi)

Japan, in from the Wilderness: Reiko Tomii’s Expanded Modern-Art History

via Hyperallergic

The Japanese-born art historian Reiko Tomii is one of those researchers who is both passionate about her subjects and recognized among her peers for her meticulous mapping of the cultural-intellectual terrain from which they emerge. An independent scholar who has lived and worked in the United States since the mid-1980s and has been based in New York for many years, Tomii has focused on the artists and art movements of post-World War II Japan, carefully classifying their evolution and ideas, as well as their constituent parts, antecedents and relevant affinities.

Although she admits that “art history is not a precise science,” her own approach is unmistakably fine-tuned, and she is an inventive thinker. The results and revelations of her method are well showcased in her new book, Radicalism in the Wilderness: International Contemporaneity and 1960s Art in Japan (MIT Press).

“Radicalism in the Wilderness: International Contemporaneity and 1960s Art in Japan” by Reiko Tomii (courtesy MIT Press) (click to enlarge)

In it, she takes on modern-art history’s familiar, canonical narrative, which, understandably, has long focused on the ideas, artists, movements, and milestone events that are linked to its roots territories in Europe and North America. However, Tomii does not take a crowbar to this history with the intent of forcing open its pantheon of recognized masters to make room for less well-known but attention-deserving modernists from Japan.

Instead, her objective reflects the interests of a still-evolving but ever more notable tendency among certain researchers and curators in the U.S., Europe and East Asia to examine modern art’s development with a broader, deeper, more inclusive scope.

Their new consideration of modern art’s story has brought such places as Mexico City, Rio de Janeiro, Tokyo, Osaka, Seoul, Delhi and Prague into sharper focus. (In the US, Alexandra Munroe, the senior curator of Asian art at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York has been a trailblazer in this effort since the mid-1990s. More recently, such museums as Tate Modern in London, the Stedelijk in Amsterdam and the Museum of Modern Art in New York have appointed new curators or developed special research programs to pursue this new outlook.)

Tomii’s own research and curatorial work have contributed significantly to this new, so-called global view of modern art’s history. In Radicalism in the Wilderness, she describes “international contemporaneity” as “a geohistorical concept, one that liberates us from the inevitable obsession with the present inherent in ‘contemporaneity’ as used in the English construction of ‘contemporary art’ (whose basic meaning is ‘art of present times’) and helps us devise an expansive historical framework” by means of which “a multicentered world art history” may be told. She argues that an understanding of this phenomenon may make room for overlooked or ignored currents in the story of modern art as it developed in 20th-century Japan after World War II. She also puts forth the related notions of what she calls “connections” and “resonances,” the meanings of which become self-evident as her study unfolds.

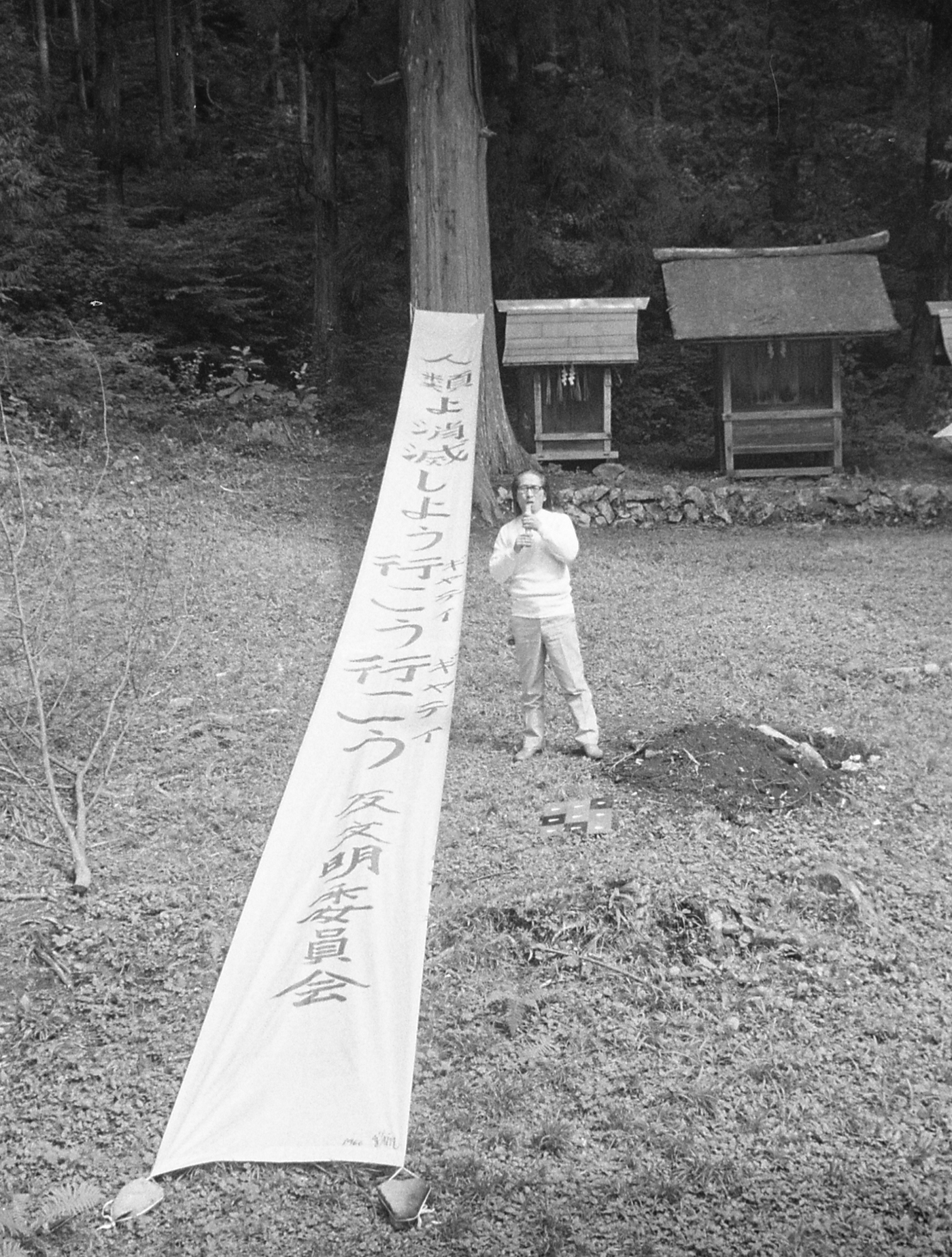

Japanese artist Yutaka Matsuzawa and his “Banner of Vanishing (Humans, Let’s Vanish, Let’s Go, Let’s Go, Gate, Gate, Anti-Civilization Committee)” (1966), at Mount Misa, Japan, 1970 (photo © Hanaga Mitsutoshi) (click to enlarge)

However, looking back at past events and examining the “international contemporaneity” of a certain moment or era from a particular vantage point is not quite the same as taking the pulse of its Zeitgeist. Instead, keen observers like Tomii are on the lookout for similar expressions, ideas, or breakthroughs that occur in different places at more or less the same time. In this way, Tomii notes, historians aiming to construct a global history of modern art must “seek out and examine linkable ‘contact points’ of geohistory,” where they will find evidence of what she calls “connections,” or “actual interactions and other kinds of links” between artists, critics, curators and other figures in the world of art, and “resonances,” which she defines as “visual or conceptual similarities” between artists’ ideas, creations or activities, even in situations in which “few or faint links existed.”

Tomii uses the examples of one solo artist and two artists’ collectives that were active in Japan in the 1960s, and whose works can be classified as conceptual art, to illustrate her observations about “international contemporaneity.” These artists’ careers offer intentional and unwitting points of contact with artists in the US and Europe. Tomii cites Yutaka Matsuzawa, who was born in 1922 in central Japan, earned a degree in architecture in Tokyo, and returned to his native region, where he later came up with art forms that reflected his disenchantment with “material civilization.”

He spent a couple of years in the US, including a stay in New York in the late 1950s, looking at art— Jackson Pollock’s paintings, Robert Rauschenberg’s mixed-media “combines” — and learning about parapsychology. Matsuzawa was interested in physics, Buddhist thought and the idea of visualizing the invisible. Back in Japan, he developed works that invited viewer-participants to “vanish” certain subjects — to make them disappear. (He once told an audience at his university, “I don’t believe in the solidness of iron and concrete. I want to create an architecture of soul, a formless architecture, an invisible architecture.”) At the exhibition Tokyo Biennale 1970: Between Man and Matter, in which both Japanese and numerous, well-known Western artists took part — a milestone, Tomii notes in retrospect, of “international contemporaneity” — Matsuzawa offered an empty room titled “My Own Death.”

Tomii also looks at the activities of The Play, a group of “Happeners,” founded in Osaka in 1967, who devised and carried out their own versions of “Happenings,” those action-as-art events that blasted the idea of the work of art as a physical object. The Play’s message, Tomii writes, “was constructive, not destructive, as their major concern was to take a ‘voyage’ away from everyday consciousness trapped in familiar space and time.” Their provocative events included erecting a huge cross made of white fabric atop a mountain (for which they intended no specific message, although it called attention to nearby urban zones’ proximity to nature), and group member Keiichi Ikemizu’s “Homo Sapiens” performance piece of 1965, in which he stood for hours like a zoo animal in a cage. A sign identified him as a representative of the human species. In 1968, The Play created a gigantic fiberglass egg, which they released into the ocean near the southernmost tip of Japan’s main island. Ikemizu told a Japanese magazine that “Voyage: Happening in an Egg” offered “an image of liberation from all the material and mental restrictions imposed upon us who live in contemporary times.”

The Play, “Voyage: Happening in an Egg” (1968), photo of performance-art event in progress (photo © The Play)

Movie directors made from wood

via Nerdcore

Great wood sculptures by well-known directors of Mike Leavitt : Alfred Hitchcock as a bird's head, Kubrick as a Shining twin with a gun, Martin Scorseseas a mashup from Travis Bickle and Raging Bull and Tarantino "ripped to shreds by his own gore." There's Wes Anderson , but Who gives a shit about Wes Anderson. (Via Superpunch )

Favio Martinez Paints a Mystical Future Realm in “Act 1: Warped Passage”

via Hi-Fructose

The word “mythological” is often used to describe the work of Mexican artist Curiot (real name Favio Martinez). Featured in Hi-Fructose Vol. 29, Curiot doesn’t apply a specific myth to the images that he paints, strongly inspired by his Mexican heritage which he hopes to uphold in his art. “The mythological creatures represent the forces of nature, the energy that flows in the universe and their relationship with the world- I like to believe they come from the spirit realm,” he told us. Curiot invites us into this mystical, somewhat futuristic place with his surreal new body of work, debuting this Saturday at Thinkspace Gallery in Los Angeles. Titled “Act 1: Warped Passage”, within these images, Curiot explains that he explores the deepest reaches of his mind: “The strangeness of life and this question of ‘what is real, are we all just part one highly elaborate simulation?'” Using a soft palette with iridescent resin finishes and hidden, glowing symbols, each piece involves intense detail, from subtle shifts in tones to different patterns. In describing the realm of his images, Curiot says: “The breaking of light will offer first site of the path within paths, at times intertwined or straight, split into two or three or four, hidden exists and glowing welcomes. As some tunnels cave in behind you, one may think, ‘what if?’ But does it really matter, each road that one takes is that of the unknown; unexplored experiences which build upon a dream, a dream we all share, that slowly unravels within our time. The mirage will remain for others to prove, vanity fades, knowledge transfers, we wake once again to another bright door.”

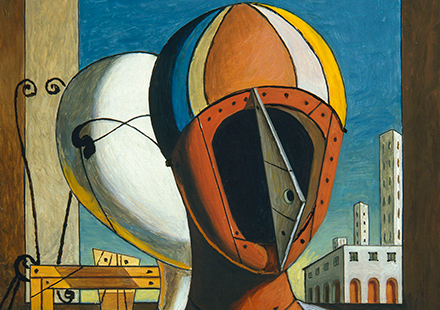

La matinée angoissante, 1912

Dorothy Parker reads "Inscription For The Ceiling Of A Bedroom"

via BrainPickings

Daily dawns another day;

I must up, to make my way.

Though I dress and drink and eat,

Move my fingers and my feet,

Learn a little, here and there,

Weep and laugh and sweat and swear,

Hear a song, or watch a stage,

Leave some words upon a page,

Claim a foe, or hail a friend —

Bed awaits me at the end.

Though I go in pride and strength,

I’ll come back to bed at length.

Though I walk in blinded woe,

Back to bed I’m bound to go.

High my heart, or bowed my head,

All my days but lead to bed.

Up, and out, and on; and then

Ever back to bed again,

Summer, Winter, Spring, and Fall —

I’m a fool to rise at all!

Animated Short: PATHS OF HATE dir.DAMIAN NENOW

"Paths of Hate" is a short tale about the demons that slumber deep in the human soul and have the power to push people into the abyss of blind hate, fury and rage.

PATHS OF HATE

Robert Lowell Reads "For the Union Dead"

“Relinquunt Omnia Servare Rem Publicam.”

The old South Boston Aquarium stands in a Sahara of snow now.Its broken windows are boarded. The bronze weathervane cod has lost half its scales. The airy tanks are dry. Once my nose crawled like a snail on the glass; my hand tingled to burst the bubbles drifting from the noses of the cowed, compliant fish. My hand draws back.I often sigh still for the dark downward and vegetating kingdom of the fish and reptile.One morning last March, I pressed against the new barbed and galvanized fence on the Boston Common.Behind their cage, yellow dinosaur steamshovels were grunting as they cropped up tons of mush and grass to gouge their underworld garage. Parking spaces luxuriate like civic sandpiles in the heart of Boston. A girdle of orange, Puritan-pumpkin colored girders braces the tingling Statehouse, shaking over the excavations, as it faces Colonel Shaw and his bell-cheeked Negro infantry on St. Gaudens’ shaking Civil War relief, propped by a plank splint against the garage’s earthquake. Two months after marching through Boston, half the regiment was dead; at the dedication, William James could almost hear the bronze Negroes breathe. Their monument sticks like a fishbone in the city’s throat. Its Colonel is as lean as a compass-needle. He has an angry wrenlike vigilance, a greyhound’s gentle tautness; he seems to wince at pleasure, and suffocate for privacy. He is out of bounds now.He rejoices in man’s lovely, peculiar power to choose life and die-- when he leads his black soldiers to death, he cannot bend his back. On a thousand small town New England greens, the old white churches hold their air of sparse, sincere rebellion; frayed flags quilt the graveyards of the Grand Army of the Republic. The stone statues of the abstract Union Soldier grow slimmer and younger each year-- wasp-waisted, they doze over muskets and muse through their sideburns . . . Shaw’s father wanted no monument except the ditch, where his son’s body was thrown and lost with his “niggers.” The ditch is nearer. There are no statues for the last war here; on Boylston Street, a commercial photograph shows Hiroshima boiling over a Mosler Safe, the “Rock of Ages” that survived the blast.Space is nearer. When I crouch to my television set, the drained faces of Negro school-children rise like balloons. Colonel Shaw is riding on his bubble, he waits for the blessèd break. The Aquarium is gone.Everywhere, giant finned cars nose forward like fish; a savage servility slides by on grease.