via Hyperallergic

Edward M. Gómez

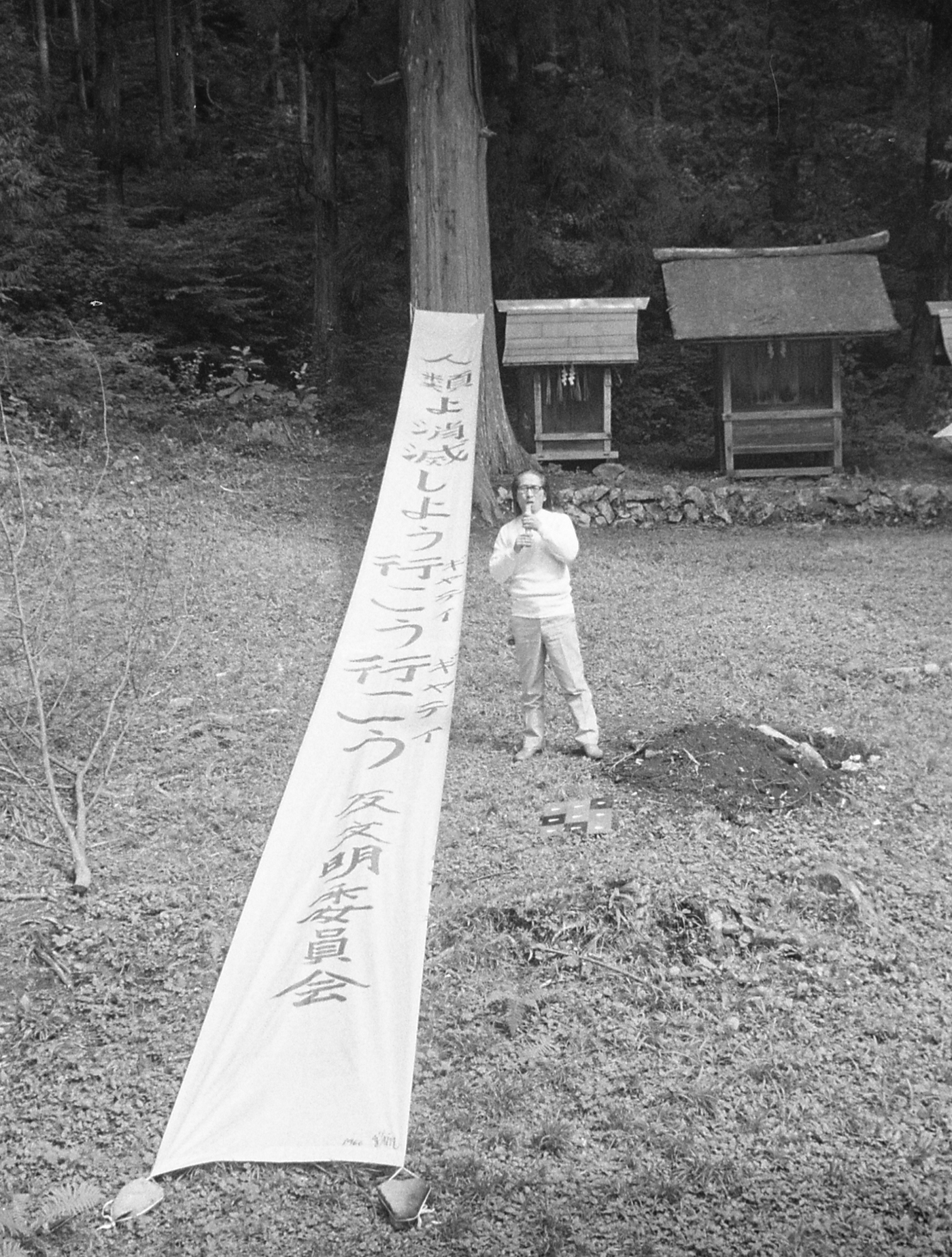

The Japanese-born art historian Reiko Tomii is one of those researchers who is both passionate about her subjects and recognized among her peers for her meticulous mapping of the cultural-intellectual terrain from which they emerge. An independent scholar who has lived and worked in the United States since the mid-1980s and has been based in New York for many years, Tomii has focused on the artists and art movements of post-World War II Japan, carefully classifying their evolution and ideas, as well as their constituent parts, antecedents and relevant affinities.

Although she admits that “art history is not a precise science,” her own approach is unmistakably fine-tuned, and she is an inventive thinker. The results and revelations of her method are well showcased in her new book, Radicalism in the Wilderness: International Contemporaneity and 1960s Art in Japan (MIT Press).

“Radicalism in the Wilderness: International Contemporaneity and 1960s Art in Japan” by Reiko Tomii (courtesy MIT Press) (click to enlarge)

In it, she takes on modern-art history’s familiar, canonical narrative, which, understandably, has long focused on the ideas, artists, movements, and milestone events that are linked to its roots territories in Europe and North America. However, Tomii does not take a crowbar to this history with the intent of forcing open its pantheon of recognized masters to make room for less well-known but attention-deserving modernists from Japan.

Instead, her objective reflects the interests of a still-evolving but ever more notable tendency among certain researchers and curators in the U.S., Europe and East Asia to examine modern art’s development with a broader, deeper, more inclusive scope.

Their new consideration of modern art’s story has brought such places as Mexico City, Rio de Janeiro, Tokyo, Osaka, Seoul, Delhi and Prague into sharper focus. (In the US, Alexandra Munroe, the senior curator of Asian art at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York has been a trailblazer in this effort since the mid-1990s. More recently, such museums as Tate Modern in London, the Stedelijk in Amsterdam and the Museum of Modern Art in New York have appointed new curators or developed special research programs to pursue this new outlook.)

Tomii’s own research and curatorial work have contributed significantly to this new, so-called global view of modern art’s history. In Radicalism in the Wilderness, she describes “international contemporaneity” as “a geohistorical concept, one that liberates us from the inevitable obsession with the present inherent in ‘contemporaneity’ as used in the English construction of ‘contemporary art’ (whose basic meaning is ‘art of present times’) and helps us devise an expansive historical framework” by means of which “a multicentered world art history” may be told. She argues that an understanding of this phenomenon may make room for overlooked or ignored currents in the story of modern art as it developed in 20th-century Japan after World War II. She also puts forth the related notions of what she calls “connections” and “resonances,” the meanings of which become self-evident as her study unfolds.